In downtown Colorado Springs, Colorado, a scaly, spiraling structure has risen from a loosely triangular site surrounded by industrial buildings on two sides and a small train yard on another. Fans of the Olympic Games know the municipality (population approximately 472,000) as Olympic City USA, home of the Olympic and Paralympic Committees’ headquarters and where more than 15,000 athletes train each year in hopes of becoming members of Team USA. Now, it is also the permanent host of the first Olympic and Paralympic Museum in the United States. Designed by New York–based architecture firm Diller Scofidio + Renfro, whose most recent cultural project was the expansion of the Museum of Modern Art, the universally accessible museum opened to the public today at the heart of a city ripe for urban densification.

The new U.S. Olympic and Paralympic Museum is split into two structures on a slightly elevated campus—the museum and a building containing a cafe, theater, and event space. A natural amphitheater and plaza separate them.

With Team USA at the center of the 60,000-square-foot museum’s collection and programming, accessibility was integral to the design in two senses. On one hand, the project had an urban mission to “connect the city to itself,” says Diller Scofidio + Renfro partner Benjamin Gilmartin, and to make an inaccessible site welcoming. On the other, it meant creating a museum where people of all abilities could access, tour, and enjoy the cultural space on the same paths.

To create urban access, the design team turned their gaze away from the site. Across the aforementioned concentration of train tracks is America the Beautiful Park and a prime opportunity to create an urban flow from a green space. Though the museum hopes to shore up developments surrounding, the architects “knew we would be on the site by ourselves for a bit and so when visitors arrive, they need to arrive at a complete place, an embracing landscape and a public space,” he explains. Thus, the site is more of a small campus, with two structures, the museum and the café/event space/theater, separated by a plaza where a man-made elevation change creates an amphitheater. From the higher portion of this plaza, the architecture firm designed a bridge to the existing park. “The need to elevate to connect across the bridge married the desire to create a topographic context around the museum, a green setting to slightly buffer the sound of train tracks,” says Gilmartin of the structure that will be completed in September and open in December.

The site is adjacent to a rail yard over which an eventual bridge by Diller Scofidio + Renfro will allow access to an existing park.

To create architectural access, they designed the entire museum as a narrative ramp. From outside, the shape of a three-story spiral can be seen beneath the aluminum-paneled façade made up of 9,000 folded anodized diamond-shaped panels, each unique. Inside, 12 galleries petal downwards from a central 40-foot-tall atrium where four overlook points help to orient visitors as they descend. Clerestory windows between each gallery pull sunlight into the atrium and create marked slashes of glass on the exterior.

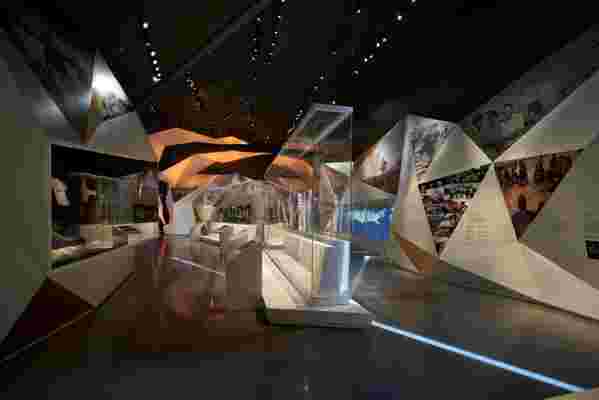

A look at the interior of the museum. While some of the interiors will allow for ample natural light to stream in, other parts will be darker to allow for a better experience.

The museum’s content itself, which includes exhibits on the history of the games as well as artifacts, and will be the home of the U.S. Olympic & Paralympic Hall of Fame, is also displayed universally. Using Radio Frequency Identification (RFID), interactive exhibitions by Gallagher Associates create a personalized experience for each guest and are designed to be enjoyed at several height levels, rather than the traditional casework that may be inaccessible to someone in a wheelchair or otherwise. “The combination of a universal path with the highly individualized experience works together well to create a very inclusive museum,” says Gilmartin, whose design was guided by advice from Olympic and Paralympic athletes on the museum board.

Interactive displays, including alpine skiing (pictured), will be available to the public.

Across the exterior plaza, the green-roof-covered secondary structure seems to lurch out of the seasonal topography that DS+R designed in collaboration with local landscape firm NES and New York–based landscape designers Hargreaves Jones (who also have offices in Cambridge and San Francisco). Within it is a flexible theater with enough space to host 26 wheelchairs (an entire Olympic hockey team’s worth), an event space with panoramic views and a 500-square-foot terrace, a café and education center, and a boardroom with Rocky Mountain vistas. Here, designing a space that was both forward-thinking, inclusive, and ecologically contextual was key, says Gilmartin. And as always, it celebrates Team USA: “The landscape brings in the mountain ecology of grasslands, woodlands, and alpine to the site,” he explains. “And its changes evoke the importance of the seasons to the Olympic and Paralympic games.”

The U.S. Olympic and Paralympic Museum will open Colorado Springs, long a city for visiting athletes, to an opportunity for all to celebrate the nation’s top physical performers. Says Tommy Schield, director of marketing and communications for the museum: “For 40 years, champions have lived and trained in Olympic City USA, and now their stories and legacies will live here forever.”